Creating a good impression

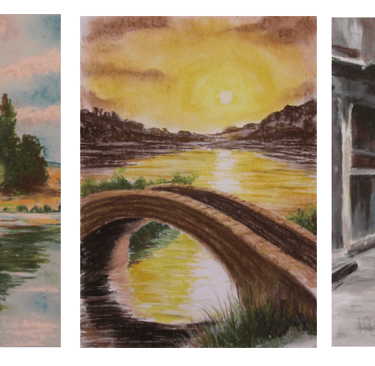

This trio of pictures appear to have little in common, yet they are a sequence of artwork I did in response to questions arising from taking part in another painter’s “study the masters” challenge.

7/29/20247 min read

It all began when I spotted a nine-part “study the masters” painting challenge that centred around the works of three artists inspired by and/or working in the period of the Impressionists whose work I really love.

Thus I signed up to the challenge to see which artists were going to be selected. Unfortunately none of the French Impressionists were included but it looked interesting so I watched some of the demonstrations in which we were encouraged to do our versions of the chosen trio.

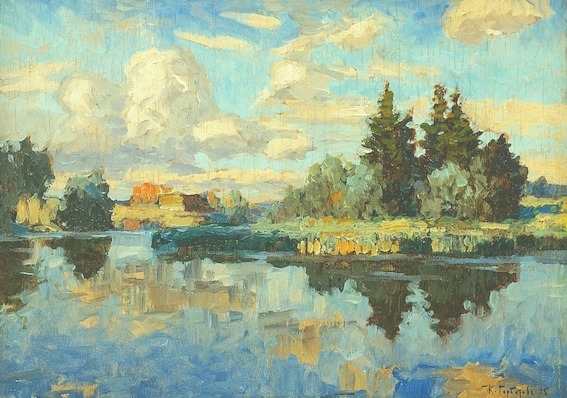

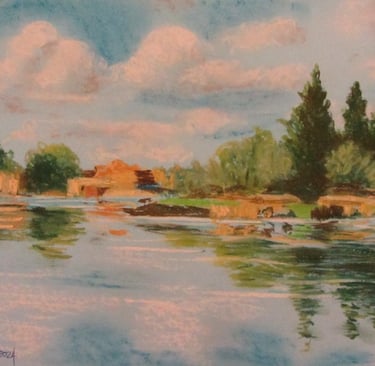

The chosen picture for the first one that I looked at was this landscape, called simply “Summer Day”, by Russian Impressionist artist Konstantin Gorbatov (1876-1945) and I confess it was the first time I had heard of him.

It turns out that it was painted in 1915 when he’d come back from visits to Europe. He’d obviously seen lots of work by the Impressionists as one could easily be forgiven for thinking that his works in this period were by the greats like Monet, Pissarro or Sisley.

I only came in half way through this section of the challenge so lots of people had already begun and were discussing the challenges they had found. Mostly it was getting bogged down in tiny details and thus not getting the spontaneity of the Impressionist style. Fully understanding what they meant, I looked for an answer and decided on a change of medium.

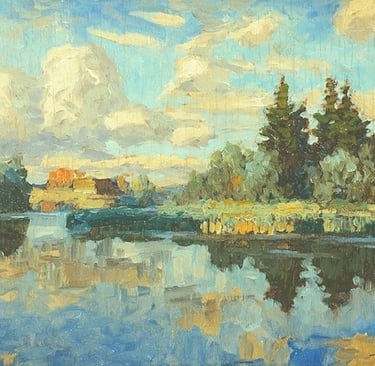

Thus instead of doing it in oils, or any painting medium, I turned to chunky sticks of soft pastels. I set myself the challenge of doing a speedy version of the picture in less than an hour by using the thickness of the pastels to replicate the wide brushstrokes Gorbatov has used in his painting.

I also chose to use a mid blue pastel paper to help in quickly creating both the sky and the water. When you choose to work in pastel on coloured paper you do have to remember that it can create problems in doing aspects of the image where you don’t want that colour to appear. However, as anyone who mixes colours knows, blue is a component of most colours in landscapes, i.e. greens and browns, which is why it was an appropriate choice.

This is my finished picture. It is not an exact copy – nor was it meant to be – but I was using it as an exercise in discovering how to create the Impressionistic effect, the immediacy, and the suggestion of the various elements of the landscape rather than getting bogged down in details.

It worked and stopped me wanting to put tiny, precise details into the painting and lose the spontaneity in the application of colours. Did I complete it in less than the allocated hour? Yes, with enough time to go and make a coffee, return, and do a few little tweaks.

I then thought that the next time I went out sketching either on my own or with my students, that I would take pastels with me instead of the usual watercolours.

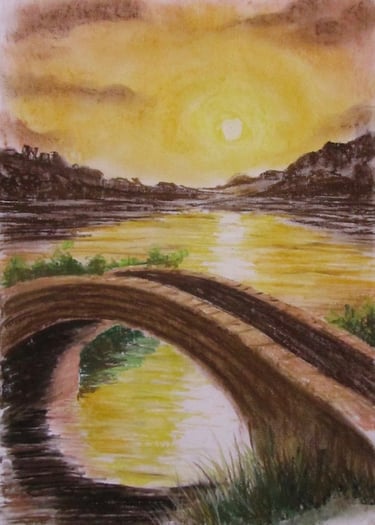

That got me thinking about the sort of "live" situation where time would be of the essence. In classic Monet-mode, my thoughts turned to the changing light effects that he was so preoccupied with capturing.

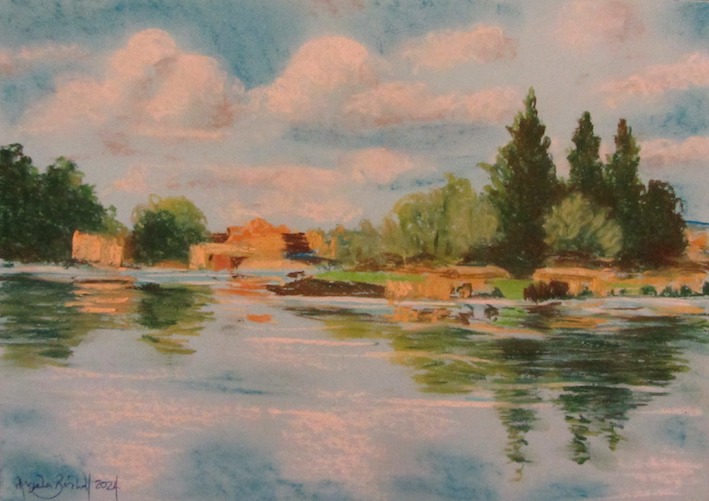

Clouds or sunrise/sunset were the two obvious starting points and so I thought if I was sat in front of a scene just as the sun was going down I would have a very limited time span in which to capture the scene.

This time I chose not to go for a coloured paper so I could see how fast I could cover the usual white paper with the sunset colours.

It’s an imaginary scene but the sort of spot that I’d happily sit in and sketch. I used soft pastels to lay down blocks of colour in quick time and only using my fingers to blend colours and soften some edges and a diffuser to sharpen other edges and to help create the horizontal ripples of the reflections in the water.

It’s not meant to be a finished, polished drawing, it’s a rapid sketch against time as if I was trying to beat the setting sun. From start to finish it took 35 minutes which isn’t bad for an A3 size picture.

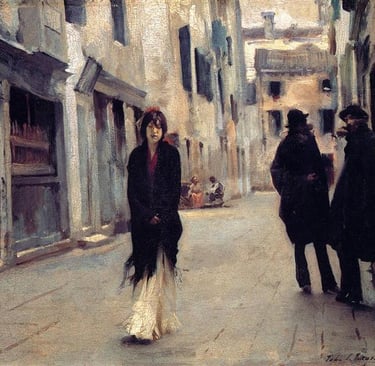

Next day I went back to the “study the masters” challenge where the third painting was being explored. This time it was the work of one of the most prolific artists John Singer Sargent: he’s said to have produced around 900 oil paintings, 2,000 watercolours and countless sketches!

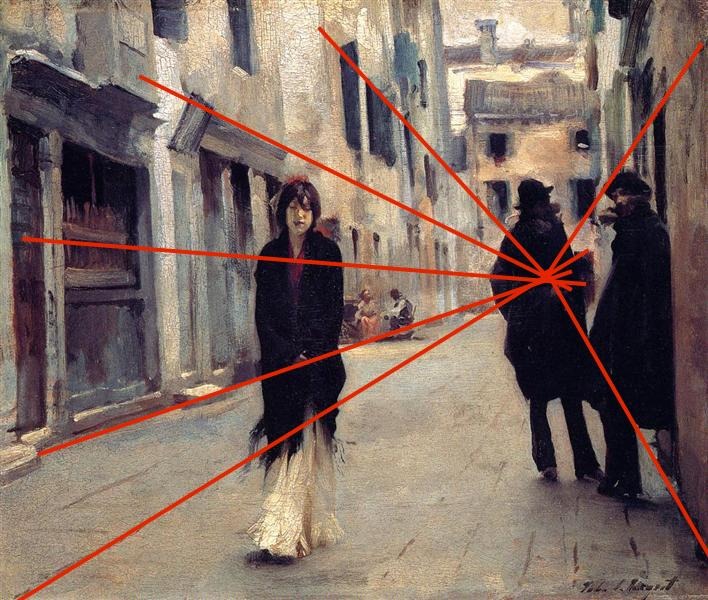

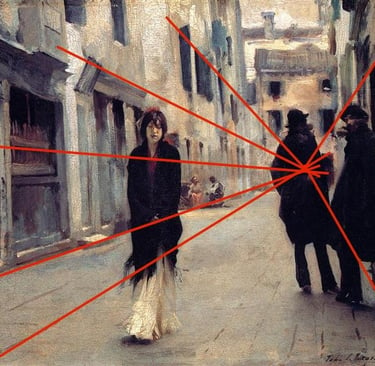

He’s well known as a portrait artist, but also did loads of cityscapes with figures in such as this one that was chosen for the challenge.

As much as it’s a “plein air” painting in typical Impressionist painting style in suggesting an “impression” of a scene, he still uses the rules of perspective in the composition of the picture. In that way he ensures that the buildings on either side of the street give you the impression that they keep going further away from you and that in reality they would stand up.

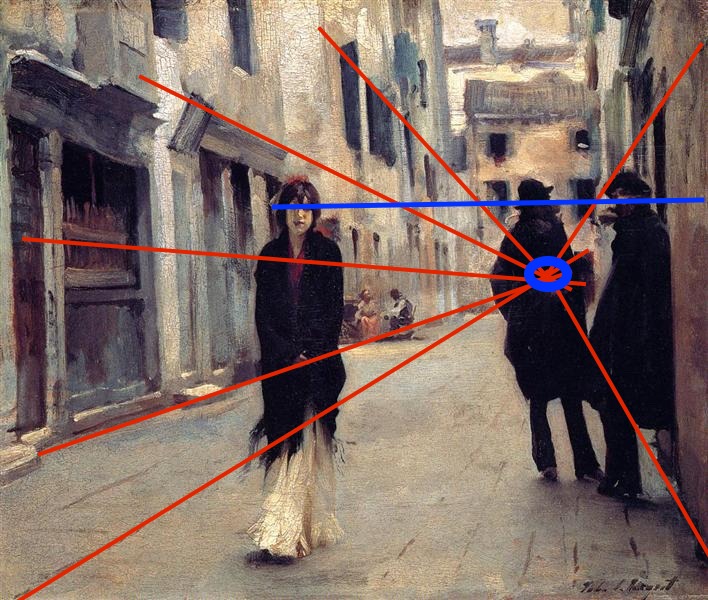

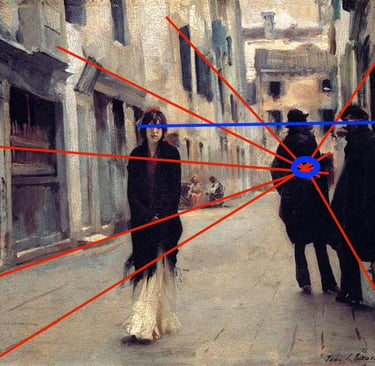

He achieves this by using a composition with a single vanishing point that ends up at chest level of the middle figure (where the red lines cross on the next photo).

To find the vanishing point, follow any of the horizontal lines on the buildings either side of the street (tops and bottoms of windows and doors, floor or roofline, etc) and you find that they slope down or up to that vanishing point. The vertical lines of walls, doors and windows will always remain vertical but the apparent horizontal lines are sloping – it confuses the left brain and is the single biggest mistake that most people make when drawing or painting buildings.

Note that the buildings at the end of the street are facing you so their horizontal lines are horizontal, not sloping.

Because the vanishing point is determined by the viewer/artist’s viewpoint, it tells you the height of his eye level (marked by blue oval shape). That suggests that in creating this picture he was probably seated, because if he was standing up, then his eye level would be at the same height as the eye level of the three main figures instead of being lower down.

Note that even though the lady is nearer the front of the scene, the heads of the three main figures are virtually in line with one another (look at the horizontal blue line).

The original painting has a proportion that is nearer a square than mine is so there is more space in mine to fill with buildings but that just gave me more opportunities to mimic the rapid brushstrokes that give that ‘impression’ of buildings rather than doing a detailed architectural painting.

They are just strokes of colours that suggest windows, doors, walls and roofs, but when you look at the picture you automatically know that that’s precisely what is being represented by those fleeting strokes. That’s because we are used to seeing buildings represented in this way in works of art but go back to the days when the Impressionists were first starting to paint this way and it was a totally different situation.

Shock, horror! How could they think that this was “proper” art?

It’s well documented that Monet called one of his paintings “Impression sunrise” and an art critic tearing their work to shreds used the term as an insult saying they were merely painting impressions of things. The group of artists thought it was great and henceforth referred to themselves as The Impressionists.

Monet probably wouldn’t have liked Sargent’s painting as the figures appear to be wearing mainly black clothing – he criticised Manet for doing the same thing! My students are used to me saying: “Don’t use black on its own; Monet wouldn’t like it!” so although I kept the clothing very dark, it is black mixed with red, blue or brown.

Being a portrait painter, Singer put more details onto the faces than many of the Impressionists did, but the brushwork is still light and fleeting enough to give that look of a picture painted ‘en plein air’ rather than in a studio.

It was fun doing my version of JSS’s picture trying to create the immediacy of the style where virtually each brushstroke is just laid down and left as it is without being worked at all, let alone overworked. The latter can cause paint to blend too much and go muddy, so the less you can work it the fresher the colours remain, especially with oils which is what he was working in.

I used acrylics which do dry quicker so you could work over the top when it’s dry but my aim was not to do that so I could keep up the same speed as you would painting outdoors. You do have to discipline yourself to not keep painting over the top and tweaking all the brushstrokes when you are not working to those time constraints but that adds to the challenge as well as the satisfaction when you achieve it.

In reality, if you were painting such a scene on location you could easily do your background of buildings and then add figures in as they appeared on the scene. You’d probably have enough time to put the two men in while they were having their chat, but you’d either have to have a photographic memory for the moving figure of the woman or get her to pose in mid stride.

Whatever else I have achieved with these three pictures, it’s spurred me on to want to go out painting en plein air again – that’s something that I just don’t do often enough. But as much as it might have answered some questions, it’s posed another one which I thought I had answered when I began this trio: I usually take watercolours when I go out sketching but after doing the first two pictures I was going to swap them for soft pastels. Now after doing the JSS picture I’m inspired to take acrylics instead . . .

Get in touch

Use the message box to drop me a line if you want to:

purchase my paintings or drawings;

discuss commissioning me to create a unique work of art especially for you;

have a question to be answered in a future Picture Perfect blog post;

join one of my face-to-face painting or drawing classes in West Lancashire or have private coaching online;

discuss a bespoke staff development event using art to encourage teamwork and leadership

Contacts

0044 77242 00779

youcandrawandpaint@gmail.com